Genetic Prognostic Factors in CLL Treated With Novel Compounds

Genetic Prognostic Factors in CLL Treated With Novel Compounds

This article was originally published by Cancer Therapy Advisor

Treatment with obinutuzumab plus venetoclax (VenG) was associated with improved outcomes compared with obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil (CGlb) among patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and established unfavorable genetic factors, according to a study published in Blood.1

“Genetic parameters are established prognostic factors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treated with chemoimmunotherapy, but are less well studied with novel compounds,” the authors wrote.

Unmutated IGHV, mutated TP53, and deletion of chromosome 17p (del[17p]) that contains the TP53 locus, are associated with progression and shorter survival among patients with CLL treated with chemoimmunotherapy. Other genetic markers have been identified that are also prognostic for outcomes.

This analysis used data from the multicenter, phase 3 CLL14 trial, which randomly assigned 432 patients with CLL to receive first-line VenG or CGlb. The analysis used fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), DNA sequencing, and next-generation sequencing to evaluate genetic prognostic factors.

CLL Experts Favor Social Distancing, but Vary on Treatment Continuation Amid Pandemic

CLL Experts Favor Social Distancing, but Vary on Treatment Continuation Amid Pandemic

This article was originally published by AJMC

The survey is the latest attempt to figure out how best to manage patients with CLL amid the pandemic, given that patients with the cancer tend to be older in age, have comorbidities, and be immunosuppressed.

In a letter to the editor of the American Journal of Hematology, corresponding author Mazyar Shadman, MD, MPH, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, in Seattle, and colleagues reported on a survey sent to 62 CLL specialists in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia. Of those, 59 responded to at least 1 question, and 44 completed the entire survey.

When asked about social distancing recommendations for patients with CLL, 32% said they would advise patients to follow the same guidelines as the WHO and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend for the general public. Twenty-one percent said they would advise patients to follow those guidelines but also limit regular outings by asking friends to pick up groceries or medications for them. Another 35% went even further, saying patients with CLL should avoid work, even if they are essential workers. The remaining 12% said they would recommend all of the above, plus wearing N95 masks and gloves outside of the house.

In terms of testing, most experts said it was not necessary to test all patients with CLL for COVID-19. Specifically, 62% of experts said they would limit testing to patients who call to and report symptoms, and another 9.5% said tests should be limited to patients who come in for an office visit and report symptoms.

Still, while clinicians generally had a low bar for what types of symptoms warranted testing. “Most favored testing patients with any levels of reported symptoms, even with limited testing availability,” Shadman and colleagues wrote. “With unlimited access, 23% recommended universal testing.”

Though their approaches to social distancing and testing were in line with recommendations for the general public, the experts expressed caution when it came to continuation of outpatient therapy. Only 14% said CLL therapy should be continued unconditionally. Most (60.5%) favored treatment discontinuation, and 25.5% said they favored continuation only based on the specific clinical situation.

However, when it came to bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKis), such as ibrutinib (Imbruvica) and acalabrutinib (Calquence), the proportion of experts favoring unconditional treatment continuation was much higher, at 44%.

Shadman and colleagues said the more favorable responses concerning BTKi continuation may be due to concern about disease flares if treatment were stopped.

“Also, there is a theoretical benefit of BTKi’s in blunting the hyperinflammatory stage of COVID-19 disease by targeting macrophages and/or inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines,” they said.

Most experts (72%) recommended against the use of intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), though the authors noted that the survey was conducted in late March and early April, “before passive antibodies in the gammaglobulin pool would be expected.”

Shadman and colleagues said additional study is warranted to better understand the optimal approach to management of patients with CLL during the pandemic.

Dr. Davids on the Potential Utility of Frontline Ibrutinib/Umbralisib in CLL and MCL

Dr. Davids on the Potential Utility of Frontline Ibrutinib/Umbralisib in CLL and MCL

This article was originally published by OncLive

Matthew S. Davids, MD, MMSc, an associate director with the Center for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia; director of clinical research, Lymphoma Program; and medical oncologist, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; and an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, discusses the potential utility of moving the combination of ibrutinib (Imbruvica) and umbralisib into the frontline setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

Findings from a phase 1/1b study presented during the 2020 European Hematology Association Annual Congress showed that ibrutinib/umbralisib elicited high response rates in CLL and MCL with a tolerable safety profile.

Updated data from the study revealed that progression-free survival and overall survival did not differ significantly from ibrutinib monotherapy in patients with MCL; however, outcomes were not negatively impacted.

In CLL specifically, the combination may have utility in the post-venetoclax (Venclexta) patient population as venetoclax is being used earlier in treatment, explains Davids.

Moving PI3K inhibitors into the frontline setting has been met with some challenges such as increased immune-mediated toxicities, says Davids.

As umbralisib appears to be a well-tolerated PI3K inhibitor, this combination may have potential utility in CLL, concludes Davids.

A 79-Year-Old Man With Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

A 79-Year-Old Man With Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

This article was originally published by Targeted Oncology

High-Risk Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Jeff Sharman, MD: Hello, my name is Jeff Sharman. I’m the Medical Director of Hematology Research for US Oncology, and I am a practicing oncologist at the Willamette Valley Cancer in Eugene, Oregon.

Today I’ve been asked to present a case of a 79-year-old gentleman with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia to address some of the treatment considerations we have in this patient population.

This particular patient is a hypothetical patient but referred to me. We’ll say that he was a 79-year-old gentleman who initially presented to his outside medical oncologist for the first time complaining of some vague intermittent abdominal pain and progressive fatigue. His past medical history is notable primarily for medically-controlled hypertension. He had a myocardial infarction 8 years ago and is on low-dose aspirin. His original CLL diagnosis was about 7 years ago, and after a period of watchful waiting, he had progressive lymphocytosis and adenopathy. He was treated with ibrutinib 420 mg daily, his symptoms improved, and he achieved a stable disease with resolution of lymphadenopathy.

Unfortunately, after 5 years of disease control on ibrutinib, he complained of increasing fatigue and decreasing appetite. Upon physical exam, he had a return of palpable lymphadenopathy, and his spleen was palpable, 4 centimeters below the costal margin. At that time, seen by an outside medical oncologist, he was started on rituximab monotherapy due to his medical comorbidities, but after 6 months on this regimen, he presents to my clinic after moving to be closer to family.

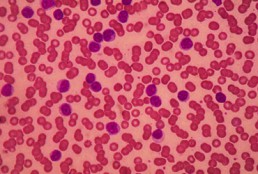

His physical exam was notable this time for palpable bilateral cervical adenopathy, right-sided inguinal adenopathy. Labs showed a white blood cell count of 55,000, predominately lymphocytes, and neutrophil count of 3100. He was anemic and thrombocytopenic, with a hemoglobin of 9.4 and platelets of 90,000, respectively. His beta-2 microglobulin was elevated, and, notably, he had a creatine clearance of just 31 mL per min.

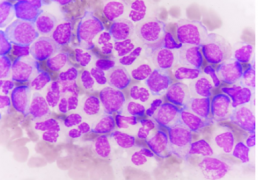

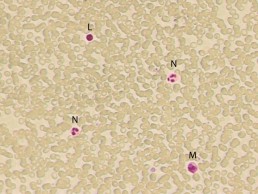

Flow cytometry confirmed the typical immunophenotype for CLL, and at this time, FISH testing was performed and, importantly, returned a deletion of 17p in a high fraction of the cells. He was Rai stage 4 with an ECOG performance status of 1. At this time, treatment was initiated with idelalisib in combination with rituximab, or I should say idelalisib was added to rituximab at this time, 150 mg PO BID.

Now this is an interesting case, and it presents a number of features that are challenging in terms of how to pick therapy in this population with significant comorbidities. I’ve been asked to address questions pertaining to both his prior management, his current situation, and so forth.

The first question I’ve been asked is to describe my initial impression of the case and what the prognosis was for this patient. You know this is a patient who has high-risk CLL. He has relapsed after ibrutinib, and he has a deletion of 17p. What that means is that chemoimmunotherapy is not going to work for this individual, so you really don’t have that much in the way of options. Then you’ve exhausted BTK inhibitors, and there’s a question of what you have left.

In this particular case, the outside provider used rituximab monotherapy probably for lack of clarity in what options might have been available; this is a patient that because of his age and comorbidities, it’s very possible this patient may ultimately pass away of their CLL, which, in contemporary CLL management, seems like a relatively rare occurrence.

When we discuss risk stratification for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, there’s a couple of things that are really important. We think about their IgHV status, which is really a measurement of how quickly the CLL is growing. What are the kinetics of growth? Then we think about the FISH status, which is how resistant it is to therapy. Deletion of 17p is a particularly noteworthy abnormality because patients with 17p have very brief responses to chemoimmunotherapy-based approaches.

Similarly, we’re seeing updates with targeted therapy, such as venetoclax, that 17p can retain adverse prognostic significance in this population. In this particular patient’s case, idelalisib had been added to the regimen. It’s noteworthy that idelalisib outcomes appear to be independent of 17p, so whether 17p is present or not, the outcomes relative to 17p don’t matter quite as much.

Transcript edited for clarity.

Case: A 79-Year-Old Man With Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Initial presentation

- A 79-year-old man presented to a new medical oncologist for the first time complaining of vague intermitted abdominal pain, and progressive fatigue

- PMH:

- Hypertension, medically controlled

- MI, 8 years ago, on 81 mg aspirin

- CLL, diagnosed 7 years ago

- After a period of watchful waiting he began treatment with ibrutinib 420 mg PO qDay; symptoms improved and achieved stable disease, resolution of lymphadenopathy

- After 5 years of disease control on ibrutinib he complained of increasing fatigue and decreased appetite, on physical exam there was return of palpable lymphadenopathy; spleen was palpable ~4 cm below costal margin

- He was started on rituximab

- Currently after 6 months on rituximab monotherapy he presents to the clinic

- PE: palpable bilateral cervical and right-sided inguinal lymphadenopathy

Clinical workup

- Labs: WBC 55,000, lymphocyte 82%, ANC 3100/mm3, Hb 9.4 g/dL, plt 90 x 109/L, LDH 220 U/L, Beta-2-microglobulin 3.9 mg/L; creatinine clearance 31 mL/min

- FC CD 5+, CD19+, CD20+ monoclonal B-cell population

- FISH: CLL probe set tested, deletion 17p

- IgHV mutational status: unmutated

- Rai stage IV; ECOG PS 1

- Treatment of idelalisib 150 mg PO BID was added to rituximab

Age, Recent Treatment, Appear to Influence Severity of COVID-19 in Patients With CLL

Age, Recent Treatment Appear to Influence Severity of COVID-19 in Patients With CLL

This article was originally published by AJMC

Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who contract coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) face more severe symptoms if they are older, though recent treatment with antileukemic agents appears to have a beneficial, rather than detrimental, effect on outcomes, a new study found. The study also suggests that the presence of comorbidities does not lead to higher mortality rates.

The retrospective analysis is based on 190 patients with CLL who had confirmed COVID-19 cases between late March and late May. The results were published in the journal Leukemia.

Corresponding author Kostas Stamatopoulos, MD, PhD, of the Center for Research and Technology Hellas, in Greece, wrote along with colleagues that CLL is a “paradigmatic example” of a malignancy that has been associated with impaired immune responses to pathogens, which they said could have negative impacts on outcomes when patients with CLL contract COVID-19. The investigators added that antileukemic treatments could further hamper the immune system’s ability to fight off a virus like SARS-CoV-2, though they said it’s not a straightforward proposition.

“On the other hand, the severity of COVID-19 and [multiorgan failure] occurrence seem to be related to clinical and laboratory parameters of inflammatory response (lymphopenia, hypoalbuminemia, higher levels of alanine aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, C-reactive protein, ferritin, and D-dimer) and markedly higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-2 receptor, IL6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor-α),” they said. “On these grounds, therapies targeting inflammation (eg, IL6/IL6R antibodies or steroids) have been used and shown potential benefit in full-blown COVID-19 patients.”

In an effort to ascertain a real-world understanding of what patients with CLL who contract the virus should expect, Stamatopoulos and colleagues analyzed the 190 colleagues based on age, gender, and comorbidities; severity of COVID-19; and whether and how long ago they had been treated with antileukemic therapies.

The investigators found a strong majority (151, or 79%) of patients presented with severe symptoms, such as requiring oxygen or admission to an intensive care unit. Patients were more likely to have severe symptoms if they were aged 65 or older.

Recent treatment appeared to make a significant difference. Only 4 in 10 patients with severe symptoms had received antileukemic treatment within the past 12 months. However, among those with mild symptoms, 76.9% had undergone recent treatment. Among those with severe symptoms, the likelihood of hospitalization was lower if they had received therapy with ibrutinib (Imbruvica).

More than one-third (36.4%) of patients with severe symptoms died from COVID-19; versus just 1 of the 38 patients with mild symptoms succumbed.

Stamatopoulos and colleagues noted that the apparent link between age and mortality among patients with CLL tracks with known data from the general population. However, they said comorbidities did not appear to have a significant impact on whether a patient had mild or severe symptoms.

As for the impact of antileukemic therapies, the authors said a disproportionate percentage of their study population had been prescribed bruton kinase inhibitors. Thus, they did not have sufficient data to compare the impact of BTK inhibitors to other types of therapy.

Still, they said their data seems to support the idea that recent antileukemic therapy is beneficial against COVD-19.

“Altogether, these data seem to further underscore the possible protective role of specific targeted therapies against a dismal evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 infection,” they said.

Long-Term Results of Ibrutinib/Umbralisib Show Efficacy in CLL and MCL

Long-Term Results of Ibrutinib/Umbralisib Show Efficacy in CLL and MCL

This article was originally published by Targeted Oncology

Matthew S. Davids, MD, associate director of the Center for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, director, Clinical Research for the Lymphoma Program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and associate professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, discusses the long-term follow-up of a phase 1/1b trial (NCT02268851) for patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) receiving ibrutinib (Imbruvica) and umbralisib.

The initial results were presented early in 2019 with about 2 years of follow-up, showing high rates of response in patients with CLL and MCL, according to Davids. There was good tolerability observed for these patients, and the investigators were able to identify the recommended phase 2 dose for umbralisib of 800 mg combined with the standard dose of ibrutinib.

The challenge with the initial report was that the follow-up for these patients was short, Davids says. The goal of the update at the 2020 European Hematology Association Congress was to present about 4 years of follow-up of the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of the high-risk patients. The investigators also looked at the rates of complete remission, which increased over time.

For patients with MCL, the median PFS was around 11 months, and the median OS was about 2 and a half years. Davids thinks that this didn’t look much different than ibrutinib monotherapy, and it is hard to tell if there is a difference between monotherapy and this combination.

Davids says the investigators saw the bigger difference in the patients with CLL compared to historical control studies. There was about an 80% 4-year PFS in the high-risk CLL population and a 4-year OS of 90%. There are still many patients on the ibrutinib and umbralisib combination. The data set highlights the efficacy and safety of dual B-cell receptor blockade and warrants further study, he believes.

CLL Advocates NZ Newsletter Issue 1

CLL Advocates NZ Newsletter Issue 1

Welcome to our first CLL Advocates newsletter. Like many organisations, we weren’t able to accomplish very much over the lockdown period. We did, however, manage a Trustees’ teleconference to shape up our strategy for the next 12 months. One of the proposals made at that meeting was a monthly newsletter, so here is the first edition.

A huge number of lay and medical articles have been written about the COVID pandemic, and, as you may have seen on our website, we’ve published a number relevant to people living with CLL. See them here. One of particular interest was a consensus statement by Australasian haematologists on management of blood cancers in the COVID pandemic (published in May’s Internal Medicine Journal). It noted that, with a mean age of diagnosis of about 70 years, CLL patients are already likely to be in a high-risk group simply because of age. Advice specifically directed to CLL patients was:

- to delay planned therapy where possible

- to consider using oral agents over IV medications so as to avoid exposure to higher risk environments such as hospital chemotherapy units, for treatment of both initial therapy, and for relapsed/refractory disease (see our recent letter to Pharmac on this matter).

New Zealand has done extraordinarily well at this stage to contain the virus, though it should be noted that vaccination, if successfully developed, may present further challenges for CLL patients.

The CLLANZ Trustees’ meeting agreed that information/education initiatives on CLL should be high on our priority list. In this regard, a review of the current management of CLL by Dr Gillian Corbett, haematologist and trustee, has been published on our website. A detailed CLL patient information booklet is also now close to sign-off and will be published shortly.

In October this year we will be staging a half day or evening combined meeting/seminar on CLL in NZ with the Leukaemia & Blood Cancer (LBC) group, with leading NZ CLL specialists. This will be ‘in person’ in Auckland and also online on Zoom so that people from around the country can join in the discussion and if desired put questions to the speakers. Details will follow soon.

To ensure we reach as many people as possible who have an interest in CLL, we encourage you to become a ‘friend’ of CLL Advocates NZ – by signing up to our newsletter here and/or joining our private Facebook group. You can apply to join the group here.

More details of anticipated activities will follow in subsequent newsletters.

Meanwhile, now that we have passed the winter solstice, and are becoming adjusted to the new ‘normal’, stay well, physically, mentally and spiritually. And please remember that as well as our advocacy role, we want to be a source of knowledge and support for New Zealanders living with CLL, and their families and supporters. To help us achieve this we would welcome and appreciate your feedback, and your thoughts on how we can best achieve our mission.

With best wishes

Neil Graham FRACP, FRCP

Executive Director

CLL Advocates NZ

Three-Drug Combo Promising Against High-Risk CLL

Three-Drug Combo Promising Against High-Risk CLL

For patients with high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), first-line therapy with a triple combination of targeted agents showed encouraging response rates in the phase 2 CLL2-GIVe trial.

Among 41 patients with untreated CLL bearing deleterious TP53 mutations and/or the 17p chromosomal deletion who received the GIVe regimen consisting of obinutuzumab (Gazyva), ibrutinib (Imbruvica), and venetoclax (Venclexta), the complete response rate at final restaging was 58. 5%, and 33 patients with a confirmed response were negative for minimal residual disease after a median follow-up of 18

Chemotherapy-Free Regimen Consisting of 3 Novel Agents for Previously Untreated, Poor Prognosis CLL

Chemotherapy-Free Regimen Consisting of 3 Novel Agents for Previously Untreated, Poor Prognosis CLL

Nearly 60% of evaluable patients with previously untreated, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) characterized by chromosomal deletion of 17p (del[17p]) and/or a deleterious TP53 mutation treated with obinutuzumab, ibrutinib, and venetoclax triplet therapy achieved either complete remission (CR) or a CR with incomplete recovery of the bone marrow, according to results of a single-arm, phase 2 study presented during the Virtual Edition of the 25th European Hematology Association (EHA) Annual Congress.

While less than 10% of patients diagnosed with CLL have disease characterized by del(17p), this biomarker is present in up to half of patients with refractory disease.2 Hence, there is an unmet need for efficacious and safe treatment regimens for this subgroup of patients. Furthermore, compounding this need is the finding that TP53 mutations, another biomarker of poor prognosis, have been reported to be present in approximately 90% of patients with disease characterized by del(17p) although only about 40% of those with TP53-mutant CLL also have del(17p).An unmutated IGHV gene is another risk factor for poor prognosis in the setting of CLL.2

Dr. Flinn on the Role of BTK Inhibitors in CLL

Dr. Flinn on the Role of BTK Inhibitors in CLL

This story was originally published on OneLive

Ian W. Flinn, MD, PhD, discusses the role of BTK inhibitors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Ian W. Flinn, MD, PhD, director of the Blood Cancer Research Program, Sarah Cannon Research Institute, discusses the role of BTK inhibitors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

BTK inhibitors such as ibrutinib (Imbruvica), acalabrutinib (Calquence), and zanubrutinib (Brukinsa) have been transformative in the treatment of patients with B-cell malignancies such as CLL, mantle cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, says Flinn.

In CLL specifically, BTK inhibitors have become a prominent frontline standard of care, adds Flinn.

Though, it is important to acknowledge that the toxicities that are associated with ibrutinib, including arthralgias, atrial fibrillation, and, though rare, significant bleeding, often lead to treatment discontinuation in patients with CLL.