Cancer Control Agency open, Prime Minister hails Blair Vining's 'tireless advocacy'

Cancer Control Agency open, Prime Minister hails Blair Vining's 'tireless advocacy'

This story was originally published on Stuff

The Prime Minister has acknowledged Blair Vining’s “tireless advocacy” as the new independent Cancer Control Agency was formally opened on Tuesday.

During Vining’s final months, as he was dying from cancer, the Southlander pushed for the Government to set up an independent cancer agency to improve cancer care for New Zealanders.

In September, a matter of weeks before Vining died, he attended an announcement in Auckland where Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern revealed the Government’s Cancer Action Plan, which included setting up a cancer agency.

On Tuesday, weeks after Vining’s death, the cancer agency has been opened.

Ardern pointed to the work of Vining when she announced the agency as open.

“I want to acknowledge those who’ve worked so hard to ensure better cancer care in New Zealand, especially Blair Vining whose tireless advocacy for the establishment of this agency has left an important legacy,” Ardern said.

”Today’s official opening marks the start of a new era for cancer care in New Zealand. The Cancer Control Agency will play a critical role in ensuring all New Zealanders get world-class cancer care, no matter who they are or where they live.”

Ardern and Minister of Health David Clark also announced the makeup of the advisory council that will support.

Included is Dr Chris Jackson, a medical director of the Cancer Society, medical oncologist, and senior lecturer at the University of Otago.

Jackson was also Vining’s doctor and the pair became close as they battled together for better cancer care in New Zealand.

Other council members include Dr Ashley Bloomfield, Dr Nina Scott, Dr Richard Sullivan, Shelly Campbell, Graeme Norton, Professor David Tipene-Leach, and Alisa Care.

Professor Diana Sarfati has been appointed by the State Services Commission as interim chief executive for the agency.

Health Minister Dr David Clark said recruitment was underway to bring the agency up to close to 40 full time staff.

“Professor Sarfati and her team will be supported by [the] advisory council made up of leading clinicians, experts and consumer representatives. The calibre of the people who have agreed to be members of the council speaks for itself, and shows just how committed the entire health sector is to making progress on cancer.”

Consultation on the Cancer Action Plan has now been completed, with nearly 400 submissions received from individuals and organisations.

The final plan will be released early next year.

Petition for Patient Voice Aotearoa: Reform Pharmac and double the Pharmac budget

Petition for Patient Voice Aotearoa: Reform Pharmac and double the Pharmac budget

There are issues involving Pharmac and how they fund medicines – Pharmac does not adopt international guidelines; it does not set a timeframe by which it will be decided if a medicine is efficacious and another timeframe when it will endeavour to fund a medicine if it is deemed to be efficacious; it needs to establish a rapid access scheme; and the budget needs to be increased as its budget is just over 5% of the Vote Health budget in comparison with the OECD average of 16%.

Sign the petition here: https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/petitions/document/PET_91080/petition-of-malcolm-mulholland-for-patient-voice-aotearoa

Follow Patient Voice Aotearoa here on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/patientvoiceaotearoa/

CLL forum with Dr Philip Thompson

CLL forum with Dr Philip Thompson

Dr Philip Thompson is a clinician and researcher at the MD Anderson Cancer Centre in Texas. In October 2019, he presented at a Leukaemia Foundation forum on the latest research and directions in CLL management and treatment.

Pharmac funds new treatment option for New Zealanders living with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

Pharmac funds new treatment option for New Zealanders living with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

This article was originally published on New Zealand Doctor

- VENCLEXTA® (venetoclax) plus rituximab will be funded from 1 December 2019 for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia who have relapsed within 36 months of previous treatment.

- Every year in New Zealand around 120 people are diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). It is the most common form of leukaemia in New Zealand.[1]

- VENCLEXTA is based on an Australian research discovery of a protein in the body called BCL-2 that helps CLL cells survive. Blocking this protein helps to kill and reduce the number of these cancer cells.[3]

AbbVie (NYSE: ABBV) New Zealand welcomes PHARMAC’s announcement that patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) whose cancer has relapsed within 36 months of previous treatment will now have funded access to VENCLEXTA® (venetoclax) in combination with rituximab, from 1 December 2019.[2]

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is a type of cancer affecting white blood cells called B-cells, and may also involve the lymph nodes. In CLL, the B-cells multiply too quickly and live too long, so that there are too many of them in the blood.[3]

Many people with chronic lymphocytic leukemia have no early symptoms. Those who do develop signs and symptoms may experience enlarged lymph nodes, fatigue, fever, night sweats, weight loss and frequent infections.[4]

Each year in New Zealand around 120 people are diagnosed with CLL, making it the most common type of leukaemia diagnosed in New Zealand.1 Although diagnosed on occasion in adults aged 35-55 years, CLL usually affects people over 60 years of age, and is diagnosed more often in men than women.[5] CLL usually develops and progresses slowly over many months or years.1

VENCLEXTA® (venetoclax) is an oral targeted treatment that works by blocking a protein in the body (“BCL-2”) that helps CLL cancer cells survive. Blocking this protein helps to kill and reduce the number of cancer cells, and may slow the spread of CLL.3

Each year in New Zealand around 120 people are diagnosed with CLL, making it the most common type of leukaemia diagnosed in New Zealand.1

Leading haematologist Dr Robert Weinkove says today’s announcement is a major step forward for New Zealanders who are living with CLL. “Many people with early-stage CLL can be safely monitored by their GP, but most eventually need treatment. It’s vital that we improve access to new targeted cancer medications so we can help New Zealanders with CLL.”

VENCLEXTA was developed as part of a research collaboration between AbbVie, Genentech, a member of the Roche Group of Companies, and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Melbourne, Australia.

AbbVie New Zealand’s General Manager, Andrew Tompkin, commended PHARMAC for recognising the unmet need of CLL patients in our community. “At AbbVie our goal is to provide medicines that make a transformational improvement in cancer treatment and outcomes for patients. Today’s news that the funding of VENCLEXTA means that patients whose CLL has returned have another option where previously their treatment choices were limited.”

[1] https://www.leukaemia.org.nz/information/about-blood-cancers/leukaemia/chronic-lymphocytic-leukaemia/

[2] https://www.pharmac.govt.nz/news/consultation-2019-09-01-venetoclax/

[3] Venclexta Consumer Information (CMI). Version 6. Updated May 2019 https://medsafe.govt.nz/consumers/cmi/v/venclexta.pdf

[4] https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia/symptoms-causes/syc-20352428 Accessed October 2019

[5] MOH Data on File 2019

Ibrutinib May Be More Effective Than Ofatumumab in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Ibrutinib May Be More Effective Than Ofatumumab in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

This article was originally published on Hematology Advisor

Final results from the phase 3 RESONATE trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01578707) suggest that ibrutinib may be more effective than ofatumumab for treating patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The results were published in the American Journal of Hematology.

Earlier results from RESONATE suggested that single-agent ibrutinib, a Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor administered once daily, has greater efficacy compared with ofatumumab for treating patients with CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma, including those with high-risk features such as 17p deletion, TP53 mutation, 11q deletion, or unmutated IGHV. For this analysis, the authors reviewed long-term safety and efficacy data.

A total of 195 patients were randomly assigned to receive ibrutinib and 196 received ofatumumab. The median duration of treatment was 41 months (range, 0.2-71.1) with ibrutinib and 5.3 months (range, 0-9.0) with ofatumumab; the planned duration with the latter, however, was 24 weeks. Of the 196 patients receiving ofatumumab, 68% (133) crossed over to the ibrutinib treatment arm.

Median overall follow-up was 74 months. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 44.1 months with ibrutinib and 8.1 months with ofatumumab (hazard ratio [HR], 0.148; P <.001). PFS was also better in the high-risk patient group that received ibrutinib compared with high-risk patients who received ofatumumab (HR, 0.110).

Overall survival was better in the ibrutinib group (67.7 vs 65.1 months), even after adjusting for crossover (HR, 0.639).

Frequently reported grade 3 or worse adverse events in the ibrutinib group included neutropenia (25%), pneumonia (21%), thrombocytopenia (10%), anemia (9%), hypertension (9%), urinary tract infection (7%), diarrhea (7%), and atrial fibrillation (6%). The prevalence of grade 3 or worse adverse events in patients receiving ibrutinib was 62% in the first year of treatment and decreased to 32% by the sixth year of treatment.

At study termination, 36.9% of patients who received ibrutinib discontinued treatment due to progressive disease, 16.4% due to adverse events, 7.7% due to withdrawal from study, 6.7% due to death, 10.3% due to investigator decision, and 22.1% due to study termination by sponsor. Of the 133 patients who crossed over from the ofatumumab group, 47 were still receiving therapy at study closure.

“These 6-year follow-up results from the RESONATE study confirm the robust and durable efficacy of ibrutinib with extended treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory CLL,” the researchers wrote.

Reference

1. Munir T, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al. Final analysis from RESONATE: Up to six years of follow-up on ibrutinib in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma [published online September 11, 2019]. Am J Hematol. doi:10.1002/ajh.25638

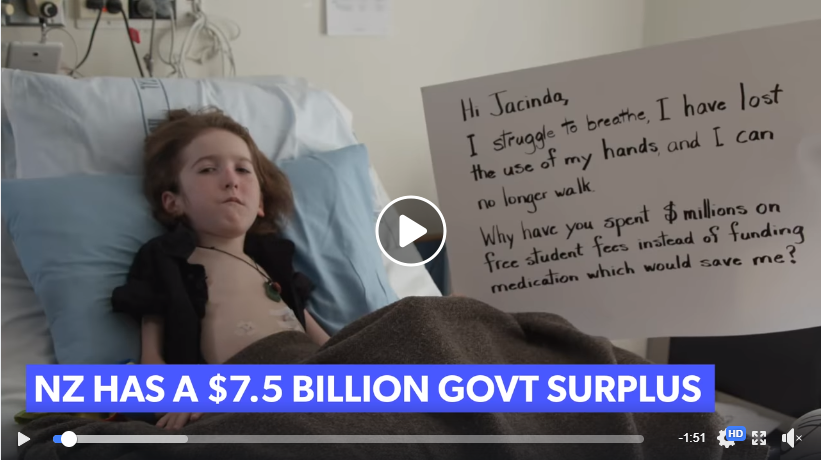

Lymphocyte count threshold for diagnosis

Lymphocyte count threshold for diagnosis

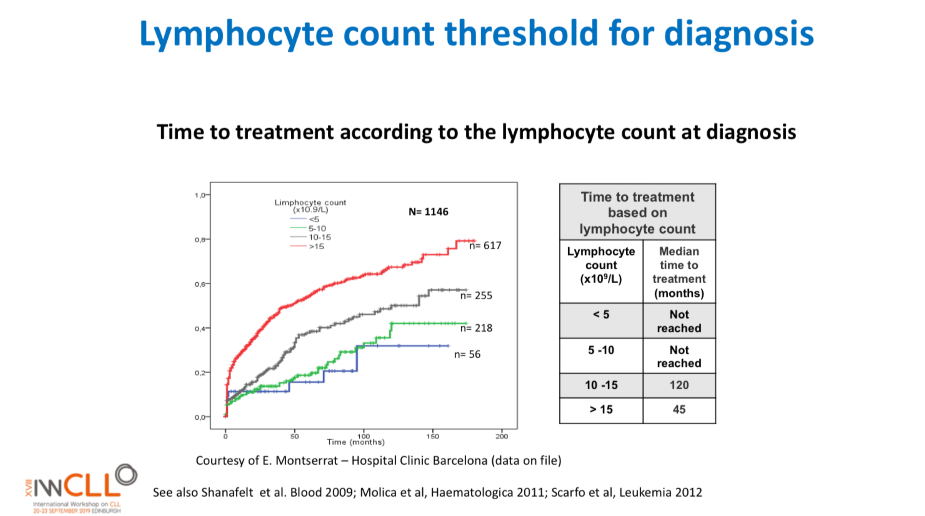

This slide calculates the likely time from being diagnosed with CLL to the commencement of formal treatment for CLL, based on lymphocyte count at diagnosis.

The time from diagnosis to treatment is started is often called the “watch and wait” period. This can be a very stressful time.

This slide uses the patient’s lymphocyte count at diagnosis to predict when treatment with medications will likely start.

The horizontal axis is months from time of diagnosis until treatment with medications is likely to start, and the vertical axis is how likely the patient is at a certain number of months after diagnosis to be on treatment (0.0 = no chance, 1.0 = certain to be having treatment). So if the patient’s lymphocyte count at diagnosis is greater than 15b/L, they have about a 50% chance of being started on treatment 50 months after diagnosis.

Pharmac to respond to CLLANZ petition

Pharmac to respond to our petition at Health Select Committee hearing this week

Go along in person or watch live on Facebook (see details below) as Pharmac presents their oral submission at the Committee’s meeting on Wednesday, 23 October 2019, from approximately 08.30am to 09.50am, at Parliament Buildings in Wellington. They will address all of the following petitions in one submission.

- Petition of Jeffrey Chan: Ask Pharmac to fund Osimertinib

- Petition of Rachel Brown for Ovarian Cancer New Zealand: Fund Lynparza and Avastin for Ovarian Cancer Patients

- Petition of Emma Crowley for Breast Cancer Aotearoa: Breast Cancer Aotearoa Coalition: Fund breast cancer drugs

- Petition of Neil Graham for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Advocates New Zealand : Fund life-saving treatments for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

- Petition of Philip Hope for Lung Foundation New Zealand: Ask Pharmac to fund innovative treatments for lung cancer

- Petition of Kenneth Romeril for Myeloma New Zealand: Fund transformative treatments for multiple myeloma patients

- Petition of Janine Yeoman: Lifesaving treatment for people who suffer from Spinal Muscular Atrophy

- Petition of Allyson Lock for the New Zealand Pompe Network: Fund Myozyme for Adults with Pompe Disease

The meeting will be open to the public, and you are welcome to attend in person or watch the live stream of the hearing on the Health Committee Facebook page here.. At this time the exact room the meeting will be held in is not decided, but you will be able to check which meeting room it will be held in closer to the date of the meeting on the Select Committee Schedule webpage here. The meeting room will also be displayed on electronic signboards inside Parliament on the day.

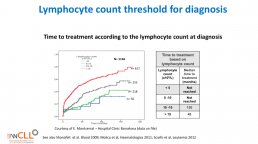

CLL Classification Systems

CLL Classification Systems

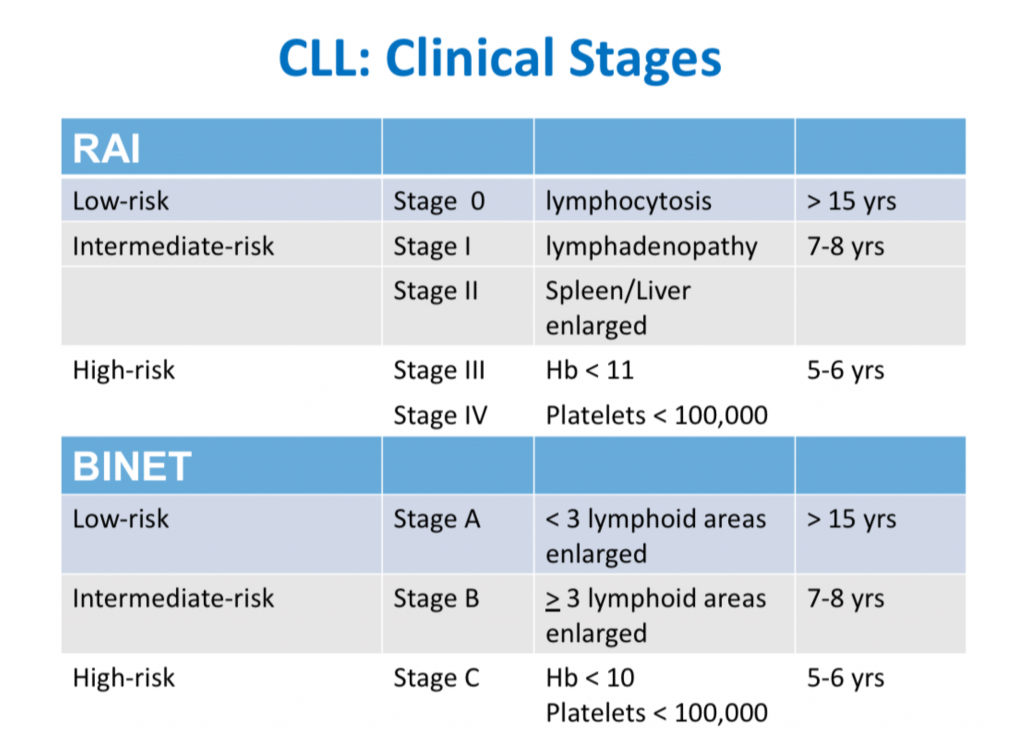

This is the third in a series of slides from the recent CLL conference in Edinburgh that may be of interest to CLL patients.

‘Rai’ and ‘Binet’ are two classification systems for CLL disease severity, developed around the same time several decades ago. Rai is a US CLL expert, and Binet is a French expert. Both systems are still used, interchangeably. Some clinicians prefer one over the other. It’s likely that another, more modern classification will be developed in the next few years.

Some explanations:

The right-hand column is known disease duration since diagnosis in the individual patient being staged.

RAI:

Lymphocytosis = increased lymphocyte numbers in the blood.

Lymphadenopathy = increase in lymph node size.

Hb = haemoglobin, a measure of the red blood cells (Hb < 11 is anaemia).

Platelets < 100,000 is a reduced platelet number

BINET:

Lymphoid areas = anatomical areas of lymph node enlargement eg enlargement of nodes under the armpits, in the groin etc.

Treatment Pathways for Active CLL

Treatment Pathways for Active CLL

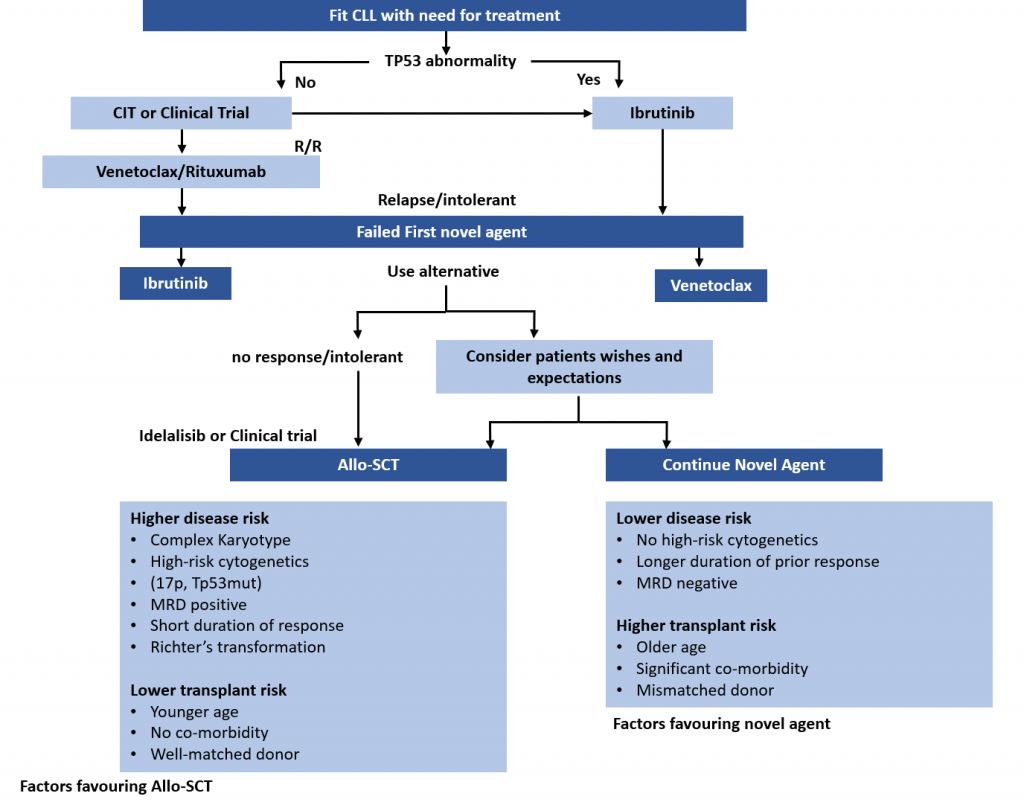

This is the second in a series of slides from the recent CLL conference in Edinburgh that may be of interest to CLL patients.

This summarises current treatment options for active CLL and lists risk factors that would influence treatment decisions.

Abbreviations:

CIT = chemoimmunotherapy, eg FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab)

Allo SCT = allogeneic stem cell transplant with stem cells from another matching person – related or unrelated. In practical terms, it is uncommonly done, can cause GVH (graft versus host disease), and is recognised as a potential cure for CLL .

MRD = minimal residual disease, ie remission.

Wake-up call for cancer agency boss Diana Sarfati

Wake-up call for cancer agency boss Diana Sarfati

My colleague haematologist Ken Romeril of Myeloma NZ has an excellent article on stuff today calling out Pharmac and the new cancer agency on their failure to factor blood cancers into their plans.